South Yorkshire Times January 19, 1957

Lundhill Disaster Centenary

Third Article

Crowd in Jocular Mood – Some Sang Hymns

Charles Dickens Visited the Stricken Pit

Mining people in the main are a phlegmatic lot and not as a rule given to emotional excesses. This may be due to the grimness of the calling and the fact that, in the “bad old days” at any rate, they were inured to tragedy. Even so it is not easy to account for, much less easy to condone, the callous behaviour of the crowd who flocked to Lundhill on the Sunday following the Thursday of the terrible disaster. A pressman telegraphing his messages to London from Barnsley said the mood on the spot was one of jest and laughter – more like a holiday crowd than a concourse assembled over the tomb of nearly 200 victims. Could this have been due to shock?

Staggered the Crowd

We proceed with his report of the scene.

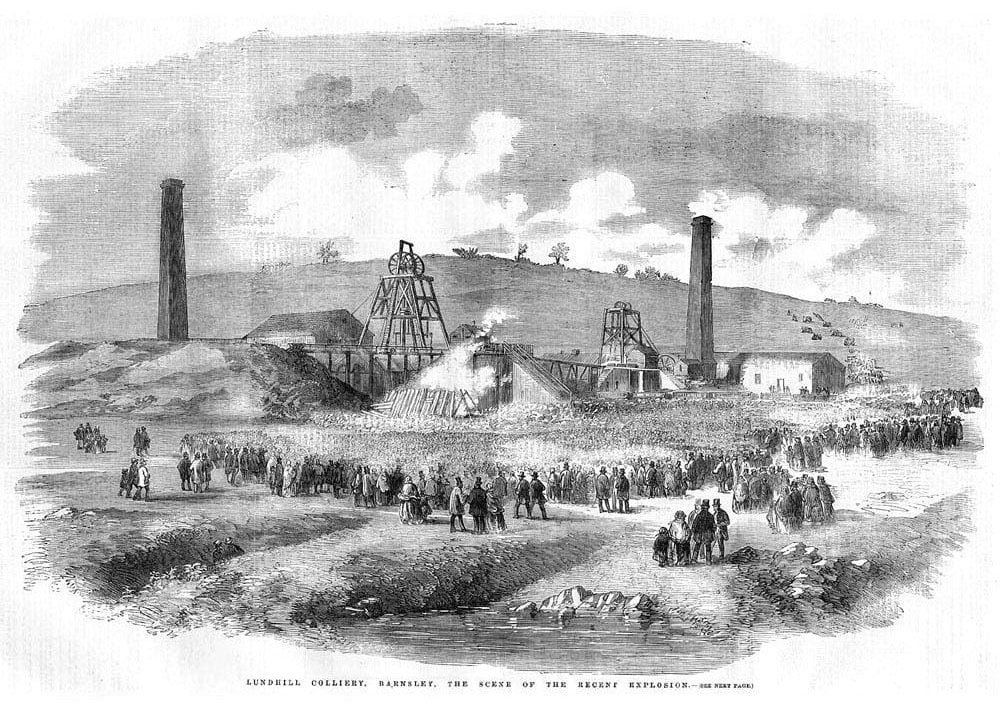

The report says, “The level ground on the steep slope between Wombwell and the colliery was crowded with people, and when the decision to close the pit was made known it naturally staggered the hopeful and appalled to silence those who had scarcely dared to hope that yet many human beings might be got up alive.

This measure showed that hope was abandoned, but the step was regarded as the most prudential. It was felt that no further search could be attempted while the fire raged, and that no one could get through the fire to the shaft.”

Representative of the press were invited to attend the consultations and the decision to close the shaft was unanimous.

A Few Sang Hymns

As is not unusual on such occasions the behavior of the masses was not exemplary.

The report said, “Every train today has brought a large number of excursionists, who by their conduct seemed bound to a fair country fête rather than the scene of a frightful calamity. Each road leading to the pit was covered with throngs of people dotting the highway for miles in every direction. The immediate neighbourhood of the colliery could only be compared to Greenwich Hill on a summer day. At 2 o’clock this afternoon they were from 10,000 to 15,000 persons on the spot, and few indeed were those who appeared to realise that they were standing immediately over the bodies of nearly 200 human beings, hurled without a moments notice into eternity.

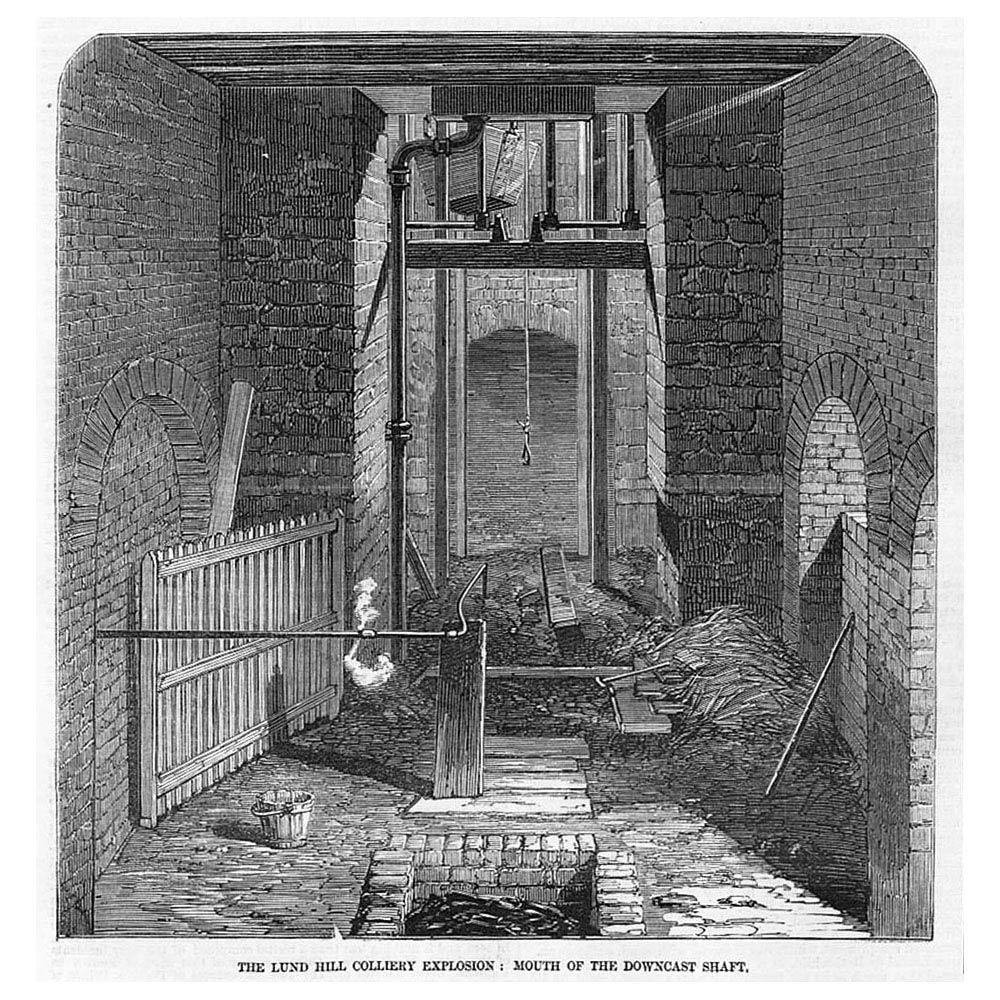

In the dense crowd the loud laugh and jest were heard incessantly. The larger part of the crowd were neighbouring pit men and their wives and children. It is difficult to understand the callousness of their conduct, contrasting with that of a few whose voices were raised occasionally in hymns. There was only one spot which spoke of death – the interior of the building over the downcast shaft, black and grim with coal dust. A grey light stealing through the timbers illuminated it mysteriously.

Dead in the Pit Bottom

The same writer says that “at the bottom of the shaft lay the bodies of eight or 10 men dragged there by those who had gone down to assist Mr Coe, Mr Maddison, Mr Webster, Mr Oakley and Mr Ellison in their dangerous search.”

Our files for March 8, 1935 contain two pictures of the Lundhill explosion taken from the “Illustrated Times” of February 28, 1857.

One picture shows Lundhill Row with relatives rushing to the blazing mine, and the other shows rescuers descending the shaft by a hopper with frantic women and children surging under the headgear.

Souvenirs of most of the big colliery explosion were produced in the form of illuminated scrolls and Lundhill was no exception. Mr Frank Walker 54, Wilkinson Road, Elsecar, had one given to him by his father, the late Mr Alf Walker, one-time deputy at Mitchell Main Colliery and secretary of Wombwell Reform Club, but unfortunately has either lost or misplaced it. He remembers however that the youngest person on the Lundhill scroll was a boy of nine, and there were several others of 10 years of age. The 189th victim was listed as “no name.”

Mr Alf Walker’s father, well known in his day as “Daddy” Walker, came from Brighton to work at Lundhill, but instead of doing so went on Wombwell Main and thus escaped the explosion. For a time his family was under the impression that he was in the disaster. Mr Frank Walker says he is under the impression that only three of the scrolls were produced.

As a matter of history the last manager of Lundhill Colliery was William Gray, who became manager at Wombwell Main after having charge of both pits. A grandson of Mr Gray, Mr William Turnbull of Winder’s place Wombwell, still has his grandfather’s diary shows that his salary for this responsible post was £250 a year!

The diary gives a day-to-day record of all events at Wombwell Main for the two decades prior to nitro firing shows that not infrequently coalface works were fined 1 shilling for leaving dirt among the coal.

The historical importance of Lundhill explosion in focusing the attention of the mining world on problems of ventilation is shown by the space given to it in a publication entitled “Conversational Mines,” a copy of which is in the possession of a young mining student, Mr Gilbert Hardcastle, of “Lea Royd” Aldham Crescent, Wombwell. The plan of Lundhill Colliery given in this work shows that the mine contained 52 doors – “as many doors as weeks in the year,” It states “Some suppose the place of the explosion to have been at the furnace which passed the whole quantity of gas from the working.”

The author of this work, a Mr William Hopton, who came from Carlton, near Barnsley, wrote:

“the ventilation at this Colliery, was so bad that I took upon myself to publish the plan and expose the system. This caused a discussion which continued for 16 weeks in the mining papers. Afterwards I received a letter from Mr Nicholas Ward, president of the Mining Institute, requesting me to become a member and offering to pay my yearly contributions. I declined the offer with thanks feel that I should frequently be required to attend meetings at Newcastle, which my means would not allow, it would have been to my advantage no doubt, had I accepted his kind offer.”

The writer tells how, following his activities of Lundhill, he was victimised and “hunted from place to place,” and his family reduced to poverty. He afterwards settled in Lancashire where he achieved some distinction in the mining world and was rewarded a prize of £275 for a thesis on “The Prevention of catastrophes in Mines”, 300 completed.

Charles Dickens visit

The fact that Charles Dickens once visited Wombwell is a new discovery. He came with a party of 400 coal merchants, literary men and others to Barnsley, and the visit to Wombwell was incidental, but the record shows that he actually went down Lundhill colliery, while the impact of the disaster on the public mind would still be strong and vivid. That was in July 1859.

The writer is indebted for this record to Miss A Guest, librarian to Barnsley Corporation who, within 10 minutes led us to the object of our search and confirmed what we had heard from another source. The party also went down Edmunds Main (Worsbrough) and the Oaks Collieries and later, having washed the grime of the mine off their countenances, attend a banquet in Barnsley Corn Exchange.

The report says the arrangements were in the end of Mr S Plimsoll, who at the time was deeply interested in the South Yorkshire coal trade.

It was at the banquet that the director of the Great Northern Railway company consented, after much persuasion, “to see that the produce of each of the South Yorkshire Collieries was sold in the name of the Colliery and not mixed with any other class of coal” – showing that the Barnsley district was intensely jealous of the quality of its product.

Barnsley or Paris?

It seems that the party haD the choice of a trip to the Yorkshire coalfield or a trip to Paris and, for some reason not easily understood, they chose Barnsley!

Under the head “Two Trains of Pleasure” the “All the Year Round” conducted by Charles Dickens contained in the issue of September 17, 1859 a racy sketch of the visit.

“Leaving King’s Cross on a lovely July morning in 1859 by special train, Doncaster was reached, the train was shunted, and the next stopping place was the Lundhill Colliery where 192 men and boys perished in 1857. Edmund’s Main and Oaks Colliery, were next visited.” After inspecting the Oaks colliery, the article proceeds, “Once more the train of pleasure was underway and this time for what is called the black Yorkshire town of Barnsley.”

Barnsley “Muck”

“As the king of pandemonium is not so dirty as he his painted, I was not surprised to find Barnsley excessively neat, clean and respectable. The town itself was white enough for all practical purposes, it was the visitors alone who required washing. There were before perhaps such a demand for soap and water to be made at the Kings Head hotel, and never had Yorkshire chambermaids been so flustered, hurried and flurried.

The crowd of grimy excursionists oozed into to the yard and satisfied themselves with tubs, butts and horse troughs. In the hotel there were 19 gentlemen at one time in one bedroom.”

Feed to follow

The account proceeds to explain that the “Cause of all this hurry and sudden desire to become purified” was the next step in the train of pleasure – a public dinner at the Town Hall (Corn Exchange) Barnsley, which is described as “substantial and profuse.” “Stray coachman served you and hosteliers placed dishes before you as if they were handling feeds of corn, but that was of little consequence.”

The narrative states that the toast at the dinner were received with all due honours, and the convivial excursionists left Barnsley about our past 6 o’clock and arrived at King’s Cross about midnight.

The same interesting event, which is headed “Free Trade in Coal; Great demonstration at Barnsley” is fully reported in the “Barnsley Record” for July 9, 1859.

The chair of the banquet was occupied by the late Mr S Plimsoll, who gave the toast “Yorkshire and the Collieries,” which was responded to by the late Mr William Stewart, one of the owners of the Lundhill colliery. Each visitor received a neat lithographic plan with descriptive letterpress of the workings of each pit.